Connecting Data to Wealth Creation

Connecting Data to Wealth Creation

The New Anatomy of Civil War: From Partisan Polls to Paramotor Attacks

======================================================================

Let’s start with the numbers, because they present a curious discrepancy. The current administration’s job approval rating is upside down by 12 points. On the economy, it’s worse, underwater by more than 15 points. On inflation, the deficit is a staggering 26.7 points. Even on signature issues like immigration and trade, the approval numbers are in negative territory. Polling on the deployment of the National Guard from one state to another against the will of local governors shows a clear majority of Americans—58 percent—in opposition.

These are not the metrics of a popular mandate. They are the vital signs of a politically vulnerable administration. And yet, the rhetoric and actions emanating from the White House don't reflect weakness. They reflect a conflict footing. The president describes American cities as “war zones.” National Guard troops from Texas land in Illinois. The pieces are being moved on a board that looks less like a political map and more like a battlefield.

This is the central paradox we need to dissect. If the actions are broadly unpopular, what does that say about the intensity of the minority who support them? Is a highly motivated, armed minority a greater catalyst for conflict than a passive, disapproving majority? The data suggests we should be taking that possibility very seriously.

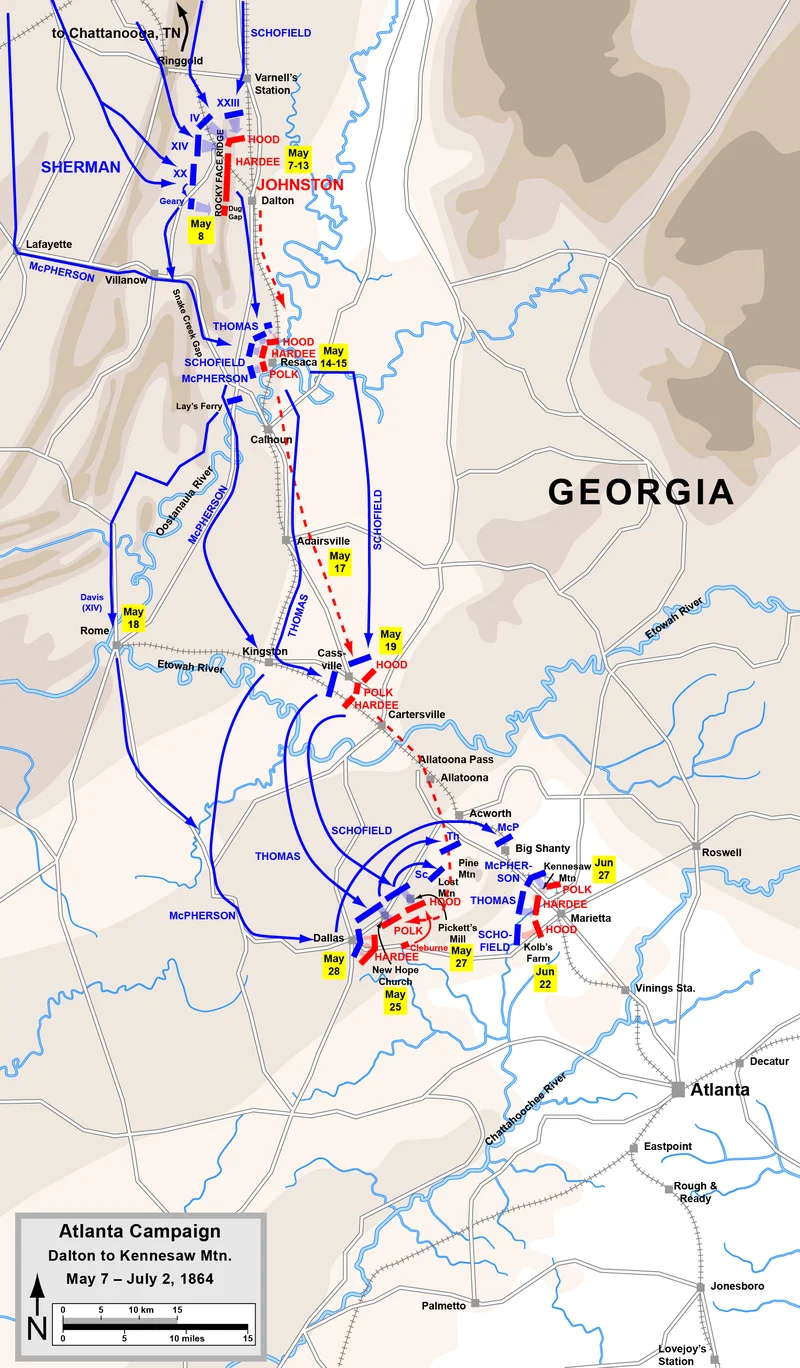

For years, the conventional model of a potential American civil conflict has been based on a profound misreading of the data. We look at the electoral map—that familiar patchwork of red and blue—and imagine a clean geographical split. The narrative assumes a war between states, a tidy replay of the 1860s. This is an analytically useless framework.

The numbers tell a different story. More than six million people voted for Donald Trump in California, a figure that dwarfs the entire Trump-voting population of a dozen smaller red states combined. A modern American conflict wouldn’t be Texas versus California. It would be neighbor versus neighbor, played out within every state, every city, and every county. It’s a conflict of ideology, not geography.

This is why the recent deployment of the National Guard is such a significant data point. Mobilizing troops to quell a riot within a single state has precedent (Eisenhower in Arkansas, Kennedy in Mississippi). But mobilizing one state’s guard to police another state, explicitly against the wishes of its governor, is something new. I've looked at historical precedents for presidential military deployments, and this cross-state mobilization against the will of local governments is a genuine outlier. It dissolves the idea of state boundaries as the primary political organizing principle and replaces it with a federal, partisan one. It functionally declares that a Republican in Oregon has more in common with a guardsman from Texas than with their Democratic governor.

This is the political infrastructure of a civil war. It’s the creation of a national-level faction that supersedes local authority. The administration claims it’s about fighting crime, but using the military for domestic policing is a category error. It’s a tactic designed to normalize the sight of soldiers on American streets and to frame political opponents not as citizens with different views, but as an internal enemy.

While the political framework for conflict solidifies in the West, the practical toolkit for it is being beta-tested elsewhere. To understand what a decentralized, low-cost civil war actually looks like, we have to look at the grim data coming out of Myanmar.

Since the military coup in 2021, the junta has been fighting a bloody war against armed resistance groups. But facing a depleted and expensive fleet of conventional aircraft, they’ve pivoted. Their new weapon of choice is the paramotor—a motorized paraglider that is terrifyingly simple and brutally effective. Paramotors: Myanmar army's lethal new weapon in civil war.

Think of it as the weaponization of the mundane. Each paramotor can carry an average of 160kg (enough for a pilot and several 120mm mortar rounds). They fly low, under 1,000 feet, and can be trained in days, not years. They run on regular fuel. One recent attack on a festival gathering lasted just seven minutes and killed 26 people. Witnesses describe the sound of the engine as being like a "chainsaw" in the night sky.

This is the critical insight. The evolution of conflict here is like the shift from mainframe computing to the personal computer. Conventional military assets—fighter jets, tanks, aircraft carriers—are the mainframes. They are immensely powerful, astronomically expensive, and controlled by a tiny handful of state actors. The paramotor, like the drone before it, is the PC. It’s cheap, accessible, and can be deployed on a massive, distributed scale. It radically lowers the barrier to entry for projecting lethal force.

The Burmese military is using these tools to achieve what they call "low-cost aerial dominance." The paramotors move slowly, around 65km/h—to be more exact, a maximum of 40 miles per hour—making them vulnerable in some contexts, but devastating against unprepared civilian targets or lightly armed militias. They are a bridge technology, more capable than a commercial drone but a fraction of the cost of a helicopter. And they are already experimenting with the next iteration: gyrocopters with heavier payloads and longer ranges.

What happens when this kind of low-cost, high-impact technology becomes available to non-state actors in a politically fractured Western country? When the political will to see your fellow citizens as an enemy converges with the accessible means to act on it?

The conversation about a second American civil war has been plagued by a failure of imagination. We envision armies and front lines, ignoring the fact that the very nature of conflict has changed. The critical variable is no longer who controls the F-35s. It's about the cost-benefit analysis of political violence.

For decades, that analysis has heavily favored stability. The state's monopoly on overwhelming force made widespread internal conflict an irrational choice. But the data points are shifting. The political rhetoric is successfully framing fellow citizens as an existential threat, and the technology of asymmetric warfare is becoming cheaper and more accessible every day. Myanmar isn't some distant, irrelevant tragedy. It's a field test for the mechanics of 21st-century civil war. The sound of that chainsaw in the sky should be a warning. The cost of organized violence is dropping, and in America, the demand for it appears to be rising.